Time-of-Flight (ToF) is a powerful technology for accurate, affordable distance sensors.

This is the second of two articles bringing you the fundamentals of Time-of-Flight technology. In the first article, we introduced the basics of ToF and how it works, and in this article, we will explain how indirect ToF sensors work in more detail.

All Time-of-Flight (ToF) sensors measure distances using the time that it takes for photons to travel between two points, from the sensor’s emitter to a target and then back to the sensor’s receiver.

Indirect and direct ToF both offer specific advantages in specific contexts. Both can simultaneously measure intensity and distance for each pixel in a scene.

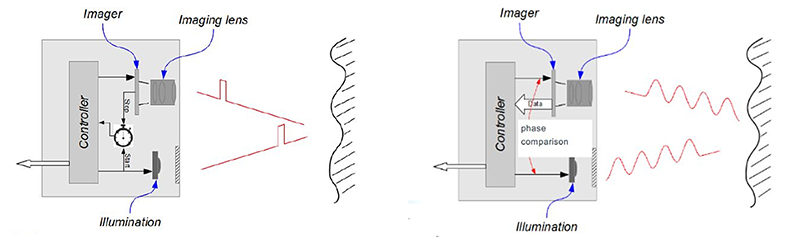

Direct ToF sensors send out short pulses of light that last just a few nanoseconds and then measure the time it takes for some of the emitted light to come back. Indirect ToF sensors send out continuous, modulated light and measure the phase of the reflected light to calculate the distance to an object.

What is a Phase, and how does it help us calculate Time-of-Flight?

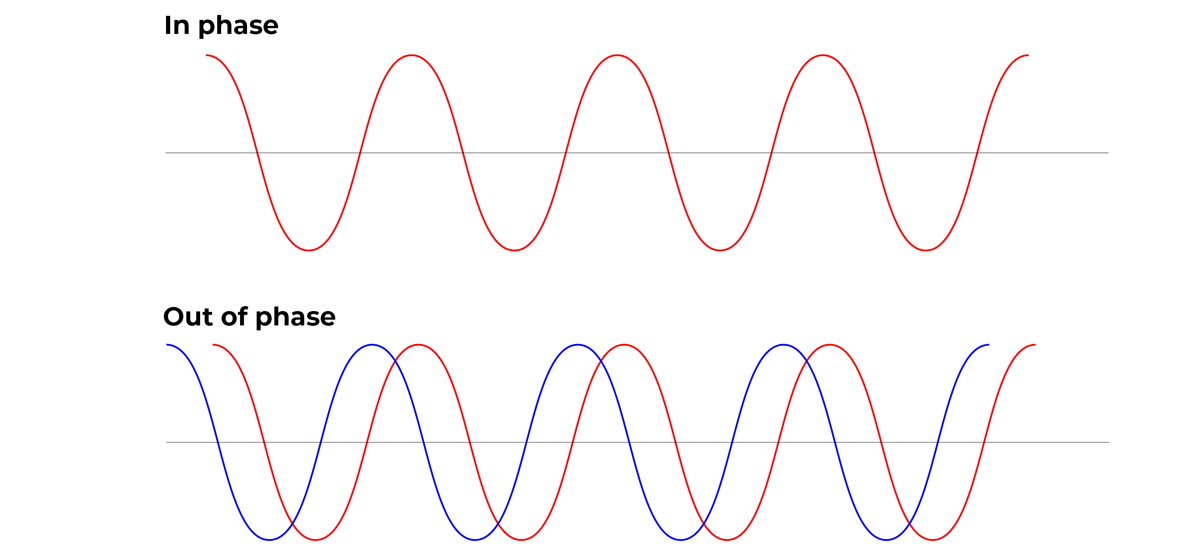

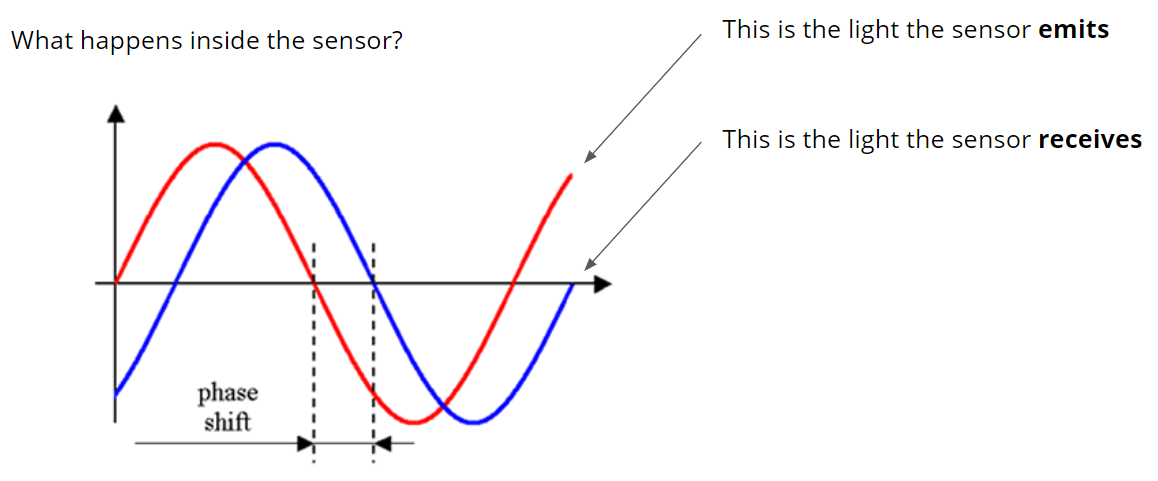

Light consists of waves with peaks and valleys that repeat in a regularly occurring cycle over time (see Figure 2). The phase of a wave describes where in the cycle the wave is and is usually expressed as an angle, with 360° representing a full cycle, 180° a half cycle, etc.

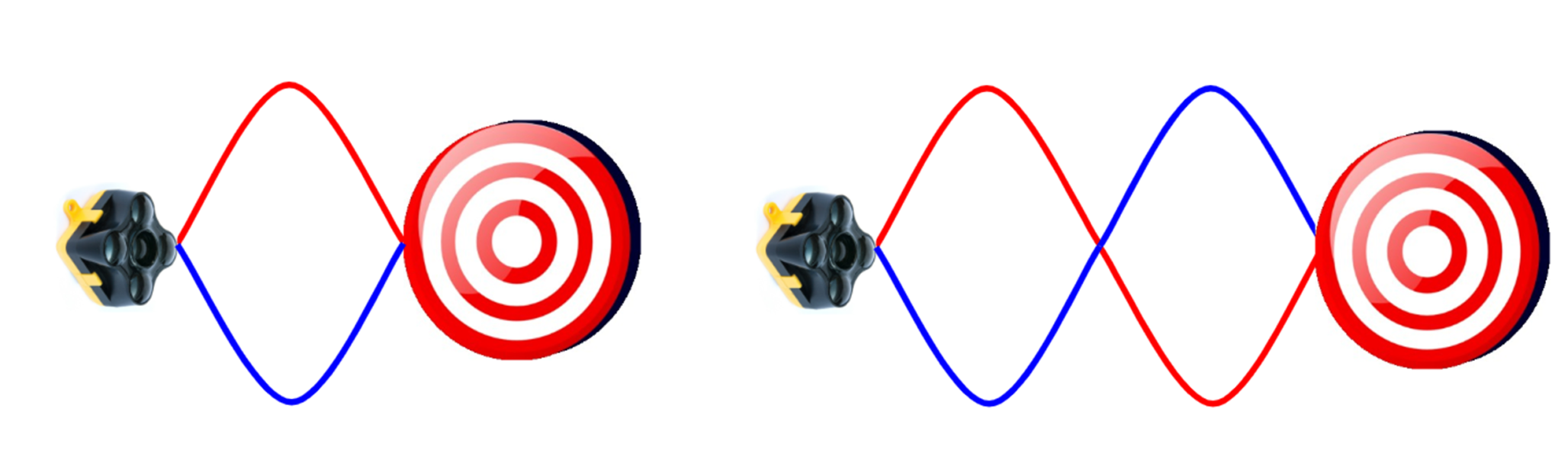

Emitted light from most sources, including the illumination source in a direct ToF sensor, consists of light that is in lots of different phases, described as ‘out of phase’.

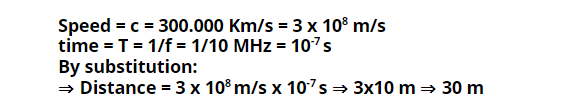

Indirect ToF sensors emit modulated light that has a set frequency and is in the same phase. The frequency of the wave determines the distance it takes for the emitted wave to complete a full cycle. For example, a 10 MHz wave takes 30 m to complete a full cycle and return to its original phase.

With a modulation at 10 MHz the maximum distance measurable for IR light round trip within a period T (before aliasing) can be extracted from the relation: distance = speed x time

As we measure the roundtrip of light, we need to divide by 2 to get the maximum measurable distance: 30 m/2 ⇒ 15 m

When an object reflects the modulated light, it returns to the sensor, which detects the shift in the phase of the returning light. Knowing the frequency of the emitted light, the phase shift of the returning light, and the speed of light allows the sensor to calculate the distance to the object.

If we point a TeraRanger Evo 60m with modulated light at 10 MHz at a target that is 7.5 m away, the wave will hit the target and be reflected to the sensor, traveling 15 m in total and completing half a wave cycle, so the phase shift is 180°. If the target were then moved to 15 m from the sensor, the wave would travel 30 m in total and complete a whole wave cycle, corresponding to a 360° phase.

The disadvantage of this method is that there can be some range ambiguity, so the modulation frequency of the emitted wave must be selected carefully. If you pointed a generic indirect ToF sensor at a target that was 22.5 m away and used a 10 MHz signal, the wave would travel 45 m in total, with a phase shift of 180°. The sensor would calculate a distance of 7.5 m because it doesn’t know that the wave has completed an extra cycle. By contrast, TeraRanger Evo features a dual frequency that prevents the range ambiguity from occurring.

How do sensors measure the returning light?

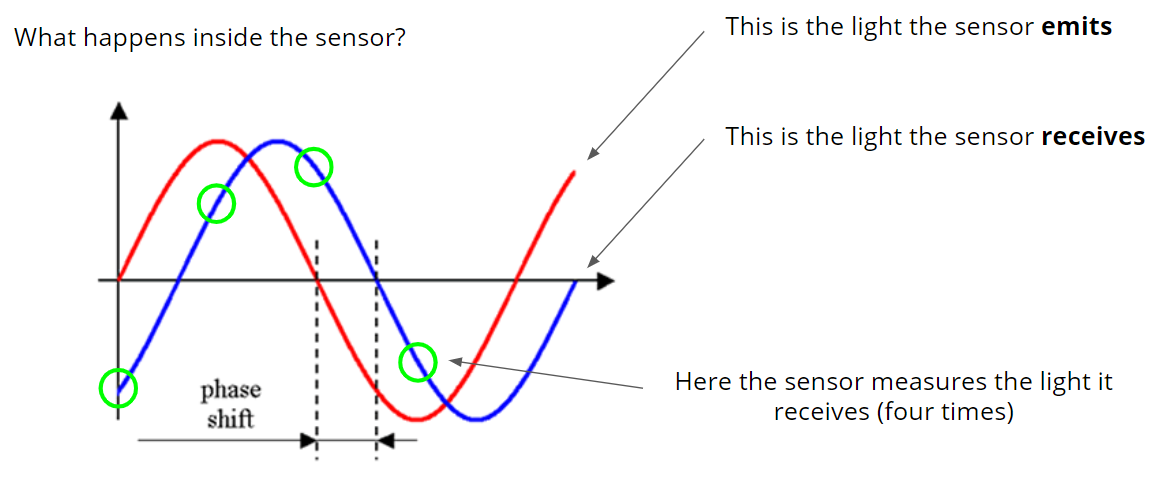

Our sensors measure the returning light on four different points. Using these four measurements, the sensor can reconstruct the returning wave and determine the phase shift compared with the emitted wave.

Environment factors that can affect indirect Time-of-Flight sensor performance

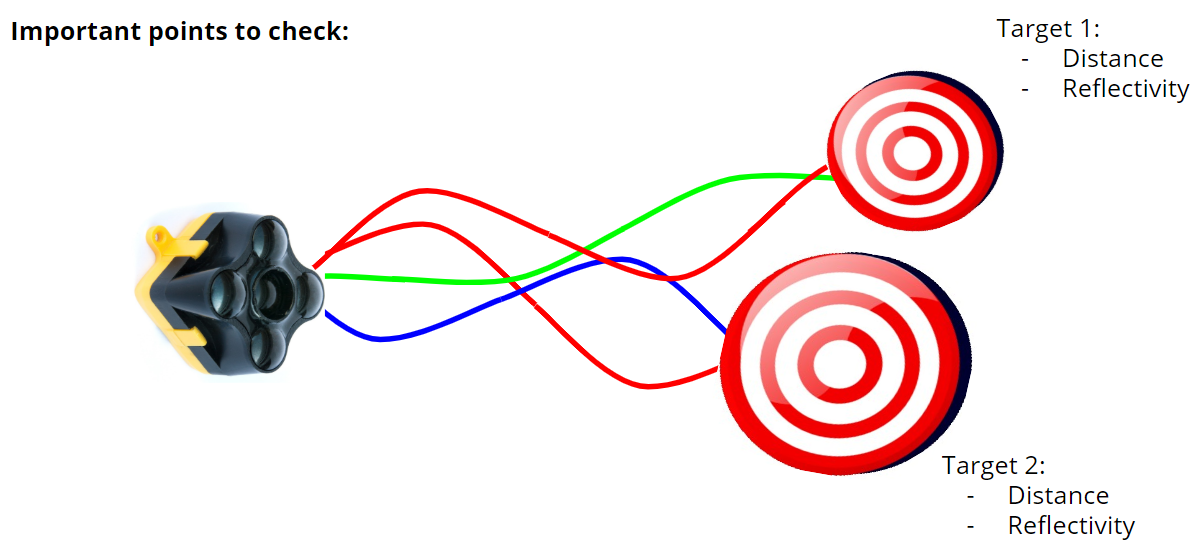

Like all technology, Indirect ToF has advantages and limitations. Light can reflect off several different objects at different distances and with different reflectivity. As a result, the sensor will receive light with different phases and intensities but won’t know that the light has come from two objects. The waves are combined as a result of the ‘superposition principle,’ and the sensor will calculate a distance that is an average of the distances in its field of view.

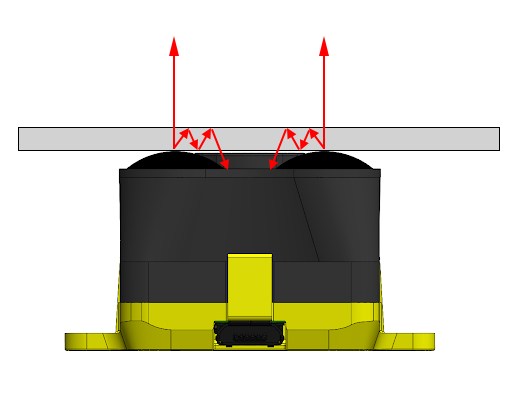

The superposition of wave phases also means extra caution has to be taken when covering indirect ToF sensors with glass. No material is 100% transparent, and light from the sensor will be scattered by the glass, with some of it returning to the sensor, resulting in the superposition of light returning from the glass and a target object.

If your application requires that your ToF sensor is covered by glass, you need to ensure that the cover does not reflect the light emitted by your sensor. Our engineers can help you find the best solution.

The advantages and applications of indirect Time-of-Flight

Despite some limitations, indirect ToF provides a range of significant advantages, including higher resolution compared with direct ToF, use of low-frequency light, and ‘slow’ illumination. It can also be scaled up to multi-pixel 3D cameras relatively easily.

Indirect ToF is a powerful and cost-effective technology. Thanks to years of research and product development, Terabee has developed technologies that push the boundaries of indirect and direct ToF to provide increased precision and range in compact modules. What’s more, Terabee ToF technologies are eye-safe and competitively priced, providing great value for their customers.

Indirect ToF sensors have a wide range of potential applications, including building safer anti-collision systems for robotics and transforming physical movements into digital data for applications like vehicle counting for smart parking, and people counting for smart building optimization.